Shrinking VS Code with name mangling

July 20, 2023 by Matt Bierner, @mattbierner

We recently reduced the size of Visual Studio Code's shipped JavaScript by 20%. That works out to a little over 3.9 MB saved. Sure that's less than some of the individual gifs from our release notes, but that's still nothing to sniff at! Not only does this reduction mean less code you need to download and store on disk, it also improves startup time because less source code has to be scanned before the JavaScript is run. Not too shabby considering we got this reduction without deleting any code and without any major refactorings in our codebase. Instead all it took was a new build step: name mangling.

In this post, I want to share how we identified this optimization opportunity, explored approaches to the problem, and eventually shipped this 20% size reduction. I want to treat this more as a case study in how we approach engineering problems on the VS Code team rather than focusing on the specifics of mangling. Name mangling is a neat trick, but may not be worth it in many codebases, and our specific approach to mangling can likely be improved on (or may not be necessary at all depending on how your project is built).

Identifying the problem

The VS Code team is passionate about performance, be that optimizing hot code paths, reducing UI re-layouts, or speeding up startup time. This passion includes keeping the size of VS Code's JavaScript small. Code size has become even more of a focus with VS Code shipping on web (https://vscode.dev) in addition to the desktop application. Actively monitoring code size keeps members of the VS Code team aware when it changes.

Unfortunately, these changes have almost always been increases. Although we put a lot of thought into what features we build into VS Code, over the years adding new functionality has necessarily grown the amount of code we ship. For instance, one of VS Code's core JavaScript files (workbench.js) is now around four times the size it was eight years ago. Now when you consider that eight years ago VS Code lacked features many would consider essential today—such as editor tabs or the built-in terminal—that increase is not perhaps as awful as it sounds, but it's not nothing either.

That 4x size increase is also after a lot of ongoing performance engineering work. Again this work largely happens because we keep track of our code size and really hate seeing it increase. We've already done many easy code size optimizations, including running our code through esbuild to minify it. Finding further savings has become increasingly challenging over the years. Many potential savings are also not worth the risks they introduce, or the extra engineering effort required to implement and maintain them. This means that we've had to watch the size of our JavaScript slowly tick upwards.

While debugging our minified source code on vscode.dev last year though, I noticed something surprising: our minified JavaScript still included tons of long identifier names, such as extensionIgnoredRecommendationsService. This surprised me. I assumed esbuild would have already shortened these identifiers. And it turns out esbuild actually does shorten identifiers in some cases through a process called "mangling" (a term JavaScript tools likely borrowed from an only roughly similar process for compiled languages).

During minification, mangling shortens long identifier names, transforming code such as:

const someLongVariableName = 123;

console.log(someLongVariableName);

To the much shorter:

const x = 123;

console.log(x);

Since JavaScript is shipped as source text, reducing the length of identifier names actually decreases the program's size. I know that optimization probably seems more than a little silly if you're coming from a compiled language, but here in the wonderful world of JavaScript we gladly take wins like this wherever we can find them!

Now before you rush out to rename all of your variables to single letters, I want to stress that optimizations like this need to be approached cautiously. If a potential optimization makes your source code less readable or maintainable, or requires significant manual work, it's almost never worth it unless it delivers truly spectacular improvements. Shaving off a few bytes here and there is nice but hardly qualifies as spectacular.

That calculus changes if we can get nice optimizations like this essentially for free, say by having our build tool do them for us automatically. And indeed, smart tools like esbuild already implement identifier mangling. That means we can keep writing our veryLongAndDescriptiveNamesThatWouldMakeEvenObjectiveCProgrammersBlush and let our build tools shorten them for us!

Even though esbuild implements mangling, by default it only mangles names when it is confident that mangling won't change the behavior of the code. After all, having a bundler break your code really stinks. In practice, this means that esbuild mangles local variable names and argument names. This is safe unless your code is doing some truly absurd things (in which case, you likely have far bigger issues than code size to worry about).

However esbuild's conservative approach means that it skips mangling many names because it can't be confident that changing them is safe. As a simple example of how things could go wrong, consider:

const obj = { longPropertyName: 123 };

function lookup(prop) {

return obj[prop];

}

console.log(lookup('longPropertyName'));

If mangling changes longPropertyName to x, the dynamic lookup on the next line will no longer work:

const obj = { x: 123 }; // Here `longPropertyName` gets rewritten to `x`

function lookup(prop) {

return obj[prop];

}

console.log(lookup('longPropertyName')); // But this reference doesn't and now the lookup is broken

Notice in the code above how we're still trying to use longPropertyName to access the property even though the property itself has been changed during mangling.

While this example is contrived, there are actually many ways these breaks can happen in real code:

- Dynamic property access.

- Serializing objects or parsing JSON to an expected object shape.

- APIs you expose (the consumers won't know about the new mangled names.)

- APIs you consume (including DOM APIs.)

Although you can force esbuild to mangle basically every single name it finds, doing so completely breaks VS Code for the reasons outlined above.

Despite this, I couldn't shake the feeling that we must be able to do better in the VS Code codebase. If we couldn't mangle every name, perhaps we could at least find some subset names we safely could.

False starts with private properties

Looking back over our minified sources, another thing that jumped out at me was how many long names I saw starting with _. By convention, this indicates a private property. Surely private properties can be safely mangled and code outside of the class would be none the wiser, right? And wait, shouldn't esbuild be doing this already for us? Yet I knew that the folks who wrote esbuild are no slouches. If esbuild wasn't mangling private properties, it was almost certainly for good reason.

As I thought about the problem more, I realized that private properties are affected by the same dynamic property lookup issue shown in the longPropertyName example above. I'm sure a smart TypeScript programmer like yourself would never write such code, but dynamic patterns are common enough in real world codebases that esbuild opts to play it safe.

Also keep in mind that the private keyword in TypeScript is really just a polite suggestion. When TypeScript code is compiled to JavaScript, the private keyword is basically removed. That means there's nothing to stop rude code outside of the class from reaching in and accessing private properties willy-nilly:

class Foo {

private bar = 123;

}

const foo: any = new Foo();

console.log(foo.bar);

Hopefully your code isn't doing questionable things like this directly, but carelessly changing property names can potentially bite you in plenty of fun unexpected ways such as with object spreads, serialization, and when distinct classes share common property names.

Thankfully I realized that with VS Code I had one huge advantage: I was working with a (mostly) sane codebase. I could make many assumptions that esbuild couldn't, such as that there are no dynamic private properties accesses or bad any accesses. This further simplified the problem I was facing.

So together Johannes Rieken (@johannesrieken) and I started to explore private property mangling. Our first idea was to try adopting JavaScript's native #private fields everywhere in our codebase. Not only are private fields immune to all of the problems detailed above, they already get mangled automatically by esbuild. Moving closer to plain old JavaScript was also appealing.

However, we quickly dismissed this approach as it would require massive (meaning risky) code changes, including removing all of our uses of parameter properties. As a relatively new feature, private fields also haven't been optimized across all runtimes yet. Using them can introduce slowdowns ranging from negligible to around 95%! Although this may be the correct change in the long run, it wasn't what we needed right now.

Next we discovered that esbuild can selectively mangle properties that match a given regular expression. However, this regular expression only matches against the identifier name. While this meant that we couldn't know if the property was declared private in TypeScript, we could try mangling all properties starting with _, which we hoped would only include private and protected properties.

Soon enough we had a working build with all _ properties mangled. Nice! This proved that private property mangling was possible and brought some decent savings, although far less than we hoped for.

Unfortunately, mangling based just on the names has some serious drawbacks, including requiring that all private properties in our codebase start with _. The VS Code codebase does not follow this naming convention consistently, and there are also a few places where we have public properties that start with _ (typically this is done when a property needs to be accessible externally but shouldn't be treated as API, such as in tests).

We also didn't feel entirely confident that the mangled code was actually correct. Sure, we could run our tests or try starting VS Code, but this was time consuming and what if we overlooked less common code paths? We couldn't be 100% sure we were only mangling private properties without touching other code. This approach seemed both too risky and too onerous to adopt.

Mangling confidently with TypeScript

Thinking about how we could feel more confident in a mangling build step, we hit on a new idea: what if TypeScript could verify the mangled code for us? Just as TypeScript can catch unknown properties accesses in normal code, the TypeScript compiler should be able to catch cases where a property has been mangled but references to it haven't been updated correctly. Instead of mangling the compiled JavaScript, we could instead mangle our TypeScript source code and then compile the new TypeScript with the mangled identifier names. The compile step on the mangled source code would give us much more confidence that we hadn't accidentally broken our code.

Not only that, but by using TypeScript, we could truly find all private properties (instead of properties that just happen to start with _). We could even use TypeScript's existing rename functionality to smartly rename symbols without changing object shapes in unexpected ways.

Eager to try out this new approach, we soon came up with new mangling build step that roughly works like this:

for each private or protected property in codebase (found using TypeScript's AST):

if the property should be mangled:

Compute a new name by looking for an unused symbol name

Use TypeScript to generate a rename edit for all references to the property

Apply all rename edits to our typescript source

Compile the new edited TypeScript sources with the mangled names

And somewhat surprisingly for such a naïve seeming approach, it worked! Well mostly at least.

While we were definitely impressed with how well TypeScript was able to generate thousands and thousands of correct edits across our entire codebase, we also had to add logic to handle a few edge cases:

-

It's not good enough for a new private property name to be unique in the current class, it also has to be unique across all superclasses and subclasses of the current class too. Once again the root cause is that TypeScript's

privatekeyword is simply a compile time decoration that doesn't actually enforce that superclasses and subclasses can't access private properties. Without care, renaming can introduce name collisions (thankfully TypeScript reports these as errors). -

In a few places in our code, subclasses made inherited protected properties public. While many of these were mistakes, we also added code to disable mangling in these cases.

After adding code for these cases, we soon had working builds. By mangling private properties, the size of VS Code's main workbench.js script went from 12.3 MB to 10.6 MB, a close to 14% reduction. This also brought a 5% speed up in code loading because less source text has to be scanned. Not bad at all given that, besides a few very minor fixes to unsafe patterns in our sources, these savings were basically free.

Learnings and further work

Mangling private properties shows that significant improvements can still be found in VS Code without resorting to massive code changes or costly rewrites. In this case, I suspect that others over the years had looked through VS Code's minified sources and wondered about those long names. However, addressing this had likely seemed impossible to do safely, or maybe just didn't seem worth a potentially massive engineering investment.

The key to our success this time was identifying a case (private properties), where name mangling would likely be safe and where the optimization would still make a significant improvement. We then thought about how to make this change as safely as possible. This meant first using TypeScript's tooling to confidently rename identifiers, and then using TypeScript again to make sure our newly mangled source code would still compile correctly. Along the way we were greatly helped by the fact that our code already followed most TypeScript best practices and also had tests in place that cover many of the common VS Code code paths. This all came together so that Joh and I could work in our spare time to ship a fairly drastic change with almost no impact to the other developers working on VS Code.

That's not the end of the mangling story though. Looking through our newly mangled and minified sources, I was crestfallen to see provideWorkspaceTrustExtensionProposals and plenty of other lengthy names. The most noteworthy were the almost 5000 occurrences of localize (the function we use for strings shown in UI). Clearly there was still room for improvement.

Using the same approach and techniques from mangling private properties, I soon identified another common code pattern that we could mangle safely with a high return on investment: exported symbol names. As long as the exports were only used internally, I felt confident we could shorten them without changing the behavior of the code.

This largely proved correct, although there were again a few complications. For instance, we had to make sure not to accidentally touch the APIs that extensions use, and also had to exempt a few symbols that were exported from TypeScript but then called from untyped JavaScript (typically these are entry points for a worker thread or process).

The export mangling work shipped last iteration, further reducing the size of workbench.js from 10.6 MB to 9.8 MB. All reductions in total, this file is now 20% smaller than it would be without mangling. Across all of VS Code, mangling removes 3.9 MB of JavaScript code from our compiled sources. Not only is that a nice reduction in download size and install size, that's also 3.9 MB less JavaScript that needs to be scanned every single time you start VS Code.

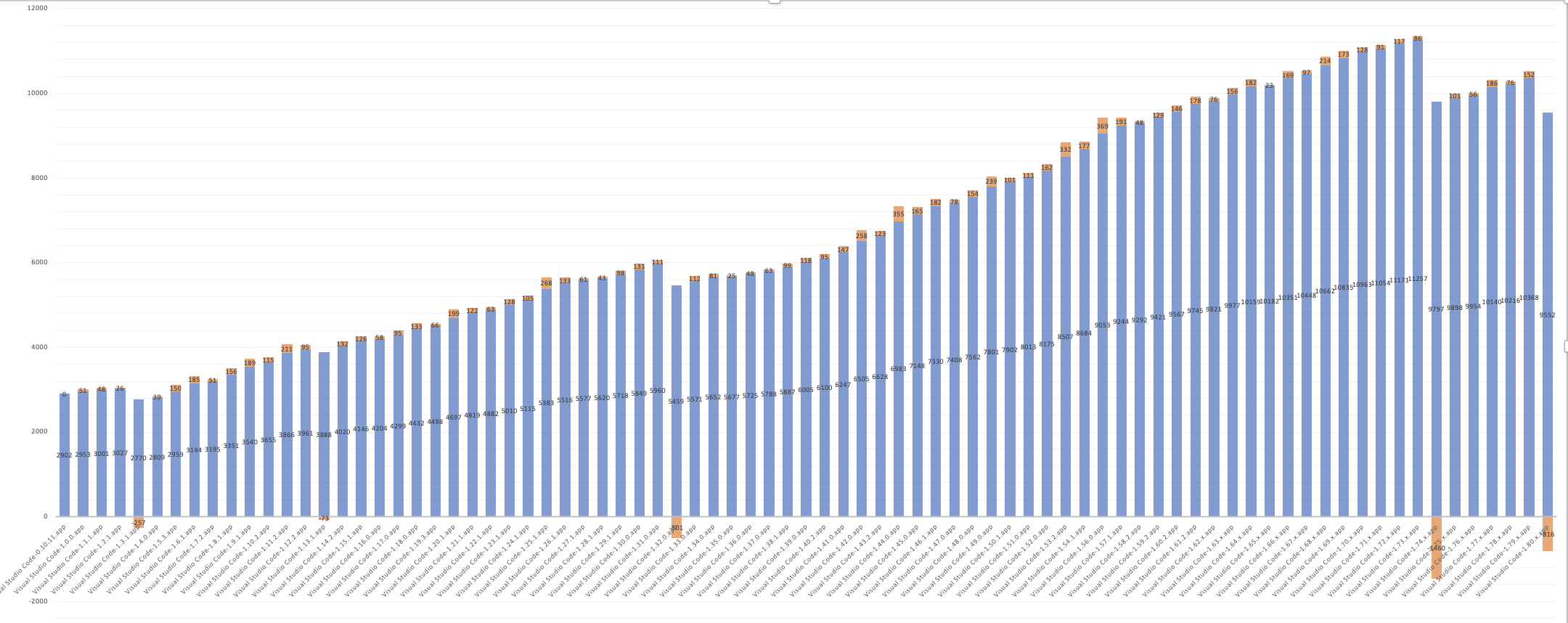

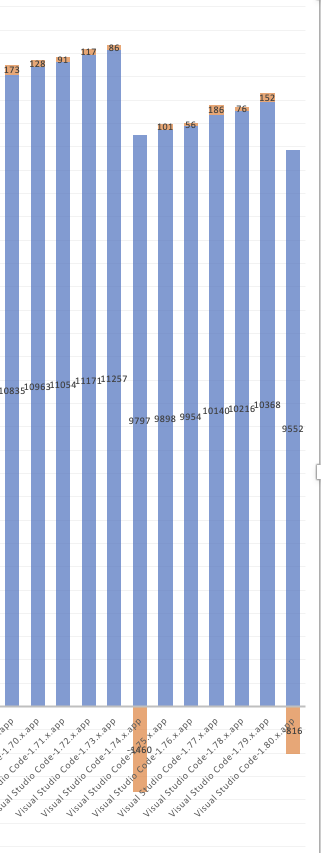

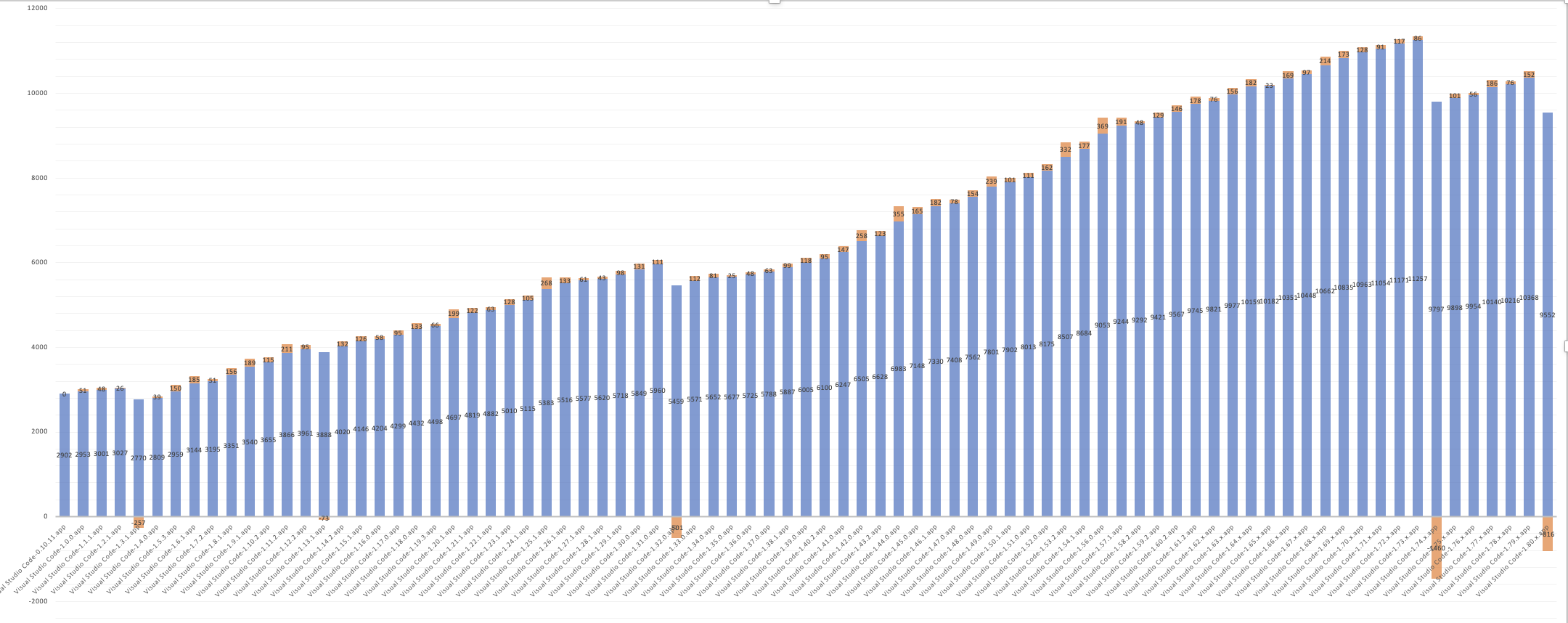

This chart shows the size of workbench.js over time. Notice the two drops on the right side. The first big drop in VS Code 1.74 is the result of mangling private properties. The second smaller drop in 1.80 is from mangling exports.

Our mangling implementation can doubtless be improved since our minified sources still contain plenty of long names. We may investigate these further if doing so seems worthwhile and if we can come up with a safe approach. Ideally, some day much of this work won't be necessary at all. Native private properties are already mangled automatically and our build tools will hopefully become better at optimizing code across our entire codebase. You can review our current mangling implementation.

We're always striving to make VS Code and our codebase better, and I think the mangling work is a great demonstration of how we approach this. Optimization is an ongoing process, not a one time thing. By continually monitoring our code size, we were aware of how it has grown over time. This awareness has doubtless help keep our code size from expanding even more than it has, and also encourages us to always be looking for improvements. Although mangling was an attractive seeming technique, it was initially too risky to seriously consider. Only once we had worked to reduce this risk, create the right safety nets, and make the cost of adopting mangling almost zero, did we finally feel confident enough to enable it in our builds. I'm really proud of the end result and just as proud of how we went about achieving it.

Happy Coding,

Matt Bierner, VS Code Team Member @mattbierner

Thank you to Johannes Rieken for his key work implementing mangling, to the TypeScript team for building the tools that let us implement mangling safely, to esbuild for their blazingly fast bundler, and to the entire VS Code team for building a codebase that is fit for optimizations like this. And last but certainly not least, a huge thanks to the V8 team and all the other JS engines for always making us look fast despite the heaps and heaps of horribly mangled JavaScript we throw their way.